Groin injuries can happen to anybody; although, they are seen most often in athletes who play sports that involve high-speed activities, such as running, jumping, and kicking. Groin injuries are especially common in soccer, football, and hockey as these sports involve sudden jumping or changing direction.

Considering that groin injuries are most common in athletes and there have been a number of sports-related groin injuries in the clinic lately, this week’s case study was focused on groin injuries, specifically, of the athletic population. The goal of this case study was to get a better understanding of how to assess someone who presents with groin pain, come up with a strategy for a differential diagnosis, as well as establish an appropriate rehab program based on the patient and the severity of the injury.

How to Approach the Diagnosis

One component of the initial assessment, that I had not given much consideration to before coming to Kinectiv, is the importance of the patient’s history. You can tell a lot from observing someone walking into the clinic or sitting in a chair. In the case of groin pain, it is important to consider the age of the patient, if they play a sport, what sport they play, and the mechanism of injury (insidious or a specific event that caused the injury). With all of this combined with their symptoms, you can begin to piece together what specific groin injury they may have. Another indicator of a groin injury is when a patient presents with the “c sign”; the patients cup their anterolateral hip with their thumb and forefinger³. This sign may indicate an injury of the groin muscles themselves or, perhaps, more to do with the attachment site on the pubic bone.

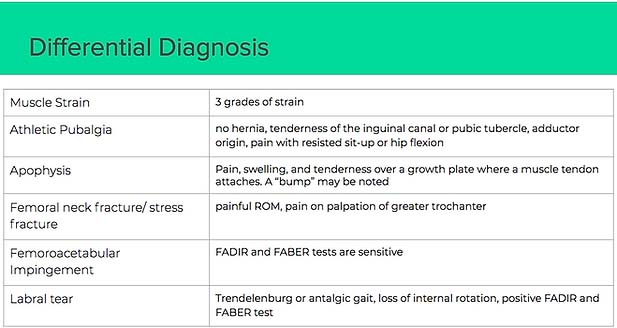

Another more challenging component of assessing a groin injury is the differential diagnosis because there are so many different injuries that present as groin pain. Therefore, it can be difficult to confidently diagnose someone. I have come up with an outline on how to differentiate between certain injuries, however, it does not cover all of the possible injuries.

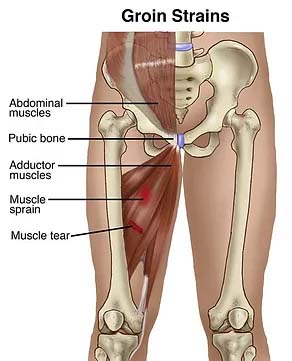

Muscle Strain

Injury or tear to the adductor muscles of the thigh. However, a hip strain can also produce referred groin pain. In addition, groin strains, depending on the severity, are graded 1,2, or 3. Produces pain on palpation of the adductors.²

- Grade 1 – symptoms include mild pain and little loss of strength and movement.

- Grade 2 – is a moderate severity injury. Symptoms include moderate pain and mild loss of strength with some tissue damage.

- Grade 3 – usually a complete tear of muscle. More severe and will affect the ability to run and jump (may require surgical intervention)

Athletic Pubalgia

Research describes athletic pubalgia, or sports hernia, and a groin strain very similarly. One way to differentiate between the two is to compare muscle strains; athletic pubalgia is more to do with injury or inflammation of the muscle tendon where it attaches to the pubic bone. Despite its name, there is no hernia, but there is tenderness of the inguinal canal, or pubic tubercle, adductor origin, as well as pain with resisted sit-up or hip flexion. Athletic pubalgia can also lead to weakening of the surrounding muscles.²

Apophysitis

Refers to inflammation or stress injury where a muscle and its tendon attaches to the area on a growth plate in a child or adolescent. Apophysitis is commonly seen in active, growing children and adolescents. It can occur in many different body parts depending on the specific repetitive activities the young athlete is commonly doing. Often seen in active young children.²

Femoral Neck Fracture/Stress Fracture

Often initially missed because it presents as exertional groin pain; however, symptoms include deep referred pain and pain with weight-bearing. Examination findings include painful range of motion and pain on palpation of the greater trochanter.²

Femoroacetabular Impingement

Related to extra bone growths along one or both of the bones that form the hip joint (cam and/or pincer). The extra growth gives the bones an irregular shape so they do not fit together perfectly; therefore, the bones rub against each other during movement. Both the FADIR and FABER test will be sensitive and the patient may complain of pain from prolonged sitting or getting in and out of the car.²

Labral Tear

A tear of the labrum can sometimes cause no signs or symptoms; however, one may experience a locking or catching sensation in the hip joint and stiffness or limited range of motion. Other symptoms include pain with weight-bearing and loss of internal rotation, which may result in an observable antalgic gait. In addition, similar to a labral tear, the FADIR and FABER tests will be positive.²

Additional Testing

These are just some examples of different groin injuries and the symptoms they present with. As you can see, there are many similar symptoms and less unique symptoms making them different. Therefore, it can be quite challenging to say for sure what is the underlying injury after the initial assessment. With all of this considered, additional testing can be very helpful in diagnosing patients with a groin injury. Initial plain radiography of the hip should include an anteroposterior view of the pelvis and a frog-leg lateral view of the symptomatic hip. Magnetic resonance imaging should be used for the detection of occult hip fractures, stress fractures, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Magnetic arthrography is the diagnosis test of choice for labral tears. Ultrasonography is a helpful diagnostic modality for patients with suspected bursitis, joint effusion, or functional causes of hip pain (i.e. snapping hip), and can be employed for therapeutic guided injections and aspirations around the hip.¹

Several injury mechanisms have been proposed for groin injuries; however, the typical groin injury is primarily related to the hip abductors. A common assumption is that strength deficits, such as abnormal hip abductor-to-lower-abdominal muscle strength ratio and lack of internal rotation, could be possible risk factors. This results in an inability of the abdominal muscles to reduce the shear forces created during hip adduction moments. In addition, adequate hip internal rotation creates shear forces across the pubic symphysis that ultimately strain the abdominal musculature along the inguinal wall.³

The following tests are a couple of ways to determine the amount of flexibility one has in the groin as well as the strength of the adductors.

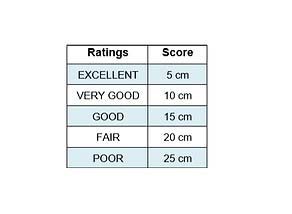

Groin Flexibility Test

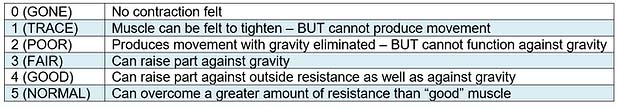

Adductor strength refers to the amount of force a muscle can produce with a single maximal effort. Many physicians will use a “sphygmomanometer” to quantify adductor strength through the use of a forceful bilateral isometric contraction of the adductor muscles. However, manual muscle testing has been used in clinical assessment of the hip muscle strength. Weakness of the musculature of the groin region, particularly of the adductors, has been identified as a risk factor for groin pain and has the ability to differentiate athletes with and without pain.

Treatment

During the first few days of recovery, the patient shoulder rest and avoid any painful exercise. Ice is always encouraged for the first few days (every 2-3 hours) to reduce pain and swelling.³

However, after a few days of rest, it is important to get moving again. Foam rolling of the groin (outer, middle, inner) and the hip flexors in combination with dynamic slow stretches will be beneficial in regards to maintaining and improving mobility of the hips. Once painless, range of motion is regained. The addition of gentle strengthening exercises is also important. Good core and pelvic stability provides a solid base for sport-specific movements and reduces the chance of adductor strains; therefore, a good core and glute program is important. Ultimately, as pain continues to diminish the strengthening exercises can keep progressing.